You have not yet added any article to your bookmarks!

Join 10k+ people to get notified about new posts, news and tips.

Do not worry we don't spam!

Post by : Anis Farhan

The skies over South and Southeast Asia darkened earlier than usual this season, but few imagined the devastation that would follow. Over the past several months, torrential rains have turned rivers into raging torrents, swallowed entire communities, and forced millions from their homes. From the mountainous valleys of northern India to the low-lying plains of the Mekong Delta, the 2024–25 monsoon has rewritten the region’s relationship with water — no longer a dependable source of life, but a force of destruction that is increasingly difficult to predict or withstand.

For generations, the monsoon has been both a blessing and a challenge for Asia. Its arrival meant the replenishment of reservoirs, the nourishment of crops, and the sustenance of rural livelihoods. But the monsoon of today is more volatile, less predictable, and significantly more destructive. Across South Asia, climate scientists have been warning that warmer global temperatures allow the atmosphere to hold more moisture, leading to heavier and more prolonged downpours. What was once a seasonal rhythm is now a series of extreme weather events, with each year bringing fresh records in rainfall, flooding, and economic losses.

The past year’s flooding events began in late 2024, when heavy rains swept across Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Malaysia, inundating farmland and damaging thousands of homes. By early 2025, the flooding had spread northwards, with parts of India, Nepal, and Pakistan experiencing deluges that would leave communities isolated for weeks. The Philippines, too, saw widespread destruction, as storm systems combined with seasonal monsoon winds to amplify the rains.

India has been among the hardest-hit nations. In Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand, mountainous terrain and fragile slopes made the region particularly vulnerable to landslides and flash floods. Entire villages were cut off as roads collapsed into gorges and bridges washed away. Helicopters were dispatched to rescue stranded pilgrims and tourists, while local communities worked alongside the army to clear debris and deliver food supplies to those marooned. In some districts, centuries-old temples and heritage sites were damaged, adding a cultural loss to the human tragedy.

In Nepal, the floods destroyed key infrastructure in the Himalayan foothills. Hydropower dams were overwhelmed, knocking out electricity for hundreds of thousands of households. Landslides buried stretches of road and even destroyed a major bridge connecting Nepal to China — a vital trade route. The economic damage here is immense, not only from the repair costs but also from the disruption to trade and industry. Rural areas, already struggling with limited access to services, saw health facilities damaged, leaving communities without basic care during the crisis.

The Philippines faced a double onslaught. Seasonal monsoon rains combined with tropical storms to produce intense flooding in Luzon and surrounding islands. Low-lying areas were submerged for days, forcing families to wade through waist-deep water to reach evacuation centers. Rice paddies, the backbone of local agriculture, were ruined in many provinces, pushing up food prices in already strained markets.

Sri Lanka endured severe flooding during the May–June rains, with thousands evacuated and tens of thousands of homes damaged. Many communities had little time to prepare, as floodwaters rose rapidly following days of continuous rain. Urban centers saw drainage systems fail under the sheer volume of water, a problem echoed in other nations across the region.

In Thailand and Malaysia, the late 2024 floods were described as the worst in years. Hundreds of thousands of people were displaced as floodwaters spread through farmlands, industrial zones, and residential areas. The damage to crops and livestock has had lasting economic consequences, particularly in rural communities dependent on agriculture.

There is no avoiding the role that climate change plays in the severity of these floods. Rising global temperatures intensify the water cycle, leading to heavier rainfall events. At the same time, melting glaciers in the Himalayas are contributing to increased river flows, especially during the monsoon. This combination of factors has created a perfect storm for disaster.

Scientists note that for every degree Celsius the planet warms, the atmosphere can hold roughly seven percent more moisture. In monsoon-prone regions, this translates into heavier downpours and a greater risk of flash flooding. While Asia has always had to contend with seasonal rains, the scale and frequency of recent disasters suggest that the region is entering a new era of climatic extremes.

One of the most telling aspects of the 2024–25 floods is the extent to which they have exposed weaknesses in infrastructure. Roads, bridges, dams, and drainage systems, many built decades ago, were never designed to withstand today’s levels of rainfall. In Nepal, the collapse of a major trade bridge cut off vital goods from reaching the interior. In India, several hydroelectric projects were forced to shut down due to landslides and debris blocking water intakes.

Urban areas, too, have suffered. Rapid and often unregulated urbanization has expanded into floodplains and wetlands, removing natural buffers against floodwaters. Drainage systems are frequently outdated or clogged, unable to cope with the sheer volume of water during peak monsoon. In cities like Manila, Colombo, and Bangkok, flash floods have become an annual occurrence, even during relatively moderate rains.

Beyond the visible destruction of buildings and infrastructure, the human toll is profound. The floods have displaced millions, forcing people into crowded temporary shelters. In such conditions, the risk of disease outbreaks — from waterborne illnesses to respiratory infections — is high. Many families have lost not only their homes but also their means of earning a living, whether through damaged farmland, lost livestock, or shuttered businesses.

Children are particularly vulnerable. In several flood-affected regions, schools have been damaged or converted into evacuation centers, interrupting education for months. For families already living on the edge of poverty, the floods have pushed them into deeper economic hardship.

While weather forecasting has improved in many parts of Asia, early warning systems remain patchy. In rural and remote areas, warnings often fail to reach communities in time, or they arrive without clear instructions on what action to take. In the case of flash floods, the window between warning and impact can be dangerously short. Regional cooperation is also limited, with neighboring countries sometimes reluctant to share real-time data on river flows or rainfall patterns due to political sensitivities.

The question now is how Asia can adapt to the new reality of extreme monsoons. Experts point to several priorities. First, infrastructure must be climate-proofed — designed and built to withstand more intense rainfall and flooding. This may mean relocating vulnerable communities or infrastructure away from high-risk zones.

Second, early warning systems need to be expanded and modernized, integrating real-time satellite data, artificial intelligence forecasting models, and community-based alert networks. Information must not only be accurate but also accessible and actionable for the people most at risk.

Third, investment in natural defenses, such as mangroves, wetlands, and reforestation, can provide critical buffers against floodwaters. These measures are cost-effective and provide environmental benefits beyond flood protection.

Finally, governments must prioritize resilience in policy and funding. International climate financing will be essential, especially for countries with limited resources to rebuild and adapt. The floods of 2024–25 have shown that reactive disaster relief is not enough; proactive adaptation is the only sustainable path forward.

The 2024–25 floods are more than a series of isolated disasters. They are a warning that the climate has shifted, and the systems that once protected communities are no longer sufficient. For Asia, the choice is stark: invest in resilience now or face even greater losses in the future.

Communities across the region have shown remarkable courage and solidarity in the face of disaster. From volunteer rescue teams in India’s Himalayan villages to farmers in the Philippines banding together to replant ruined fields, the human spirit has shone through the floodwaters. Yet courage alone cannot hold back the tide. Only coordinated action — across borders, sectors, and societies — will ensure that the monsoon of the future remains a source of life, not destruction.

This article is based on current events and publicly available data. It aims to provide a factual overview and analysis of the 2024–25 monsoon floods in South and Southeast Asia. Any resemblance to specific individuals’ personal accounts is coincidental.

Two Telangana Women Die in California Road Accident, Families Seek Help

Two Telangana women pursuing Master's in the US died in a tragic California crash. Families urge gov

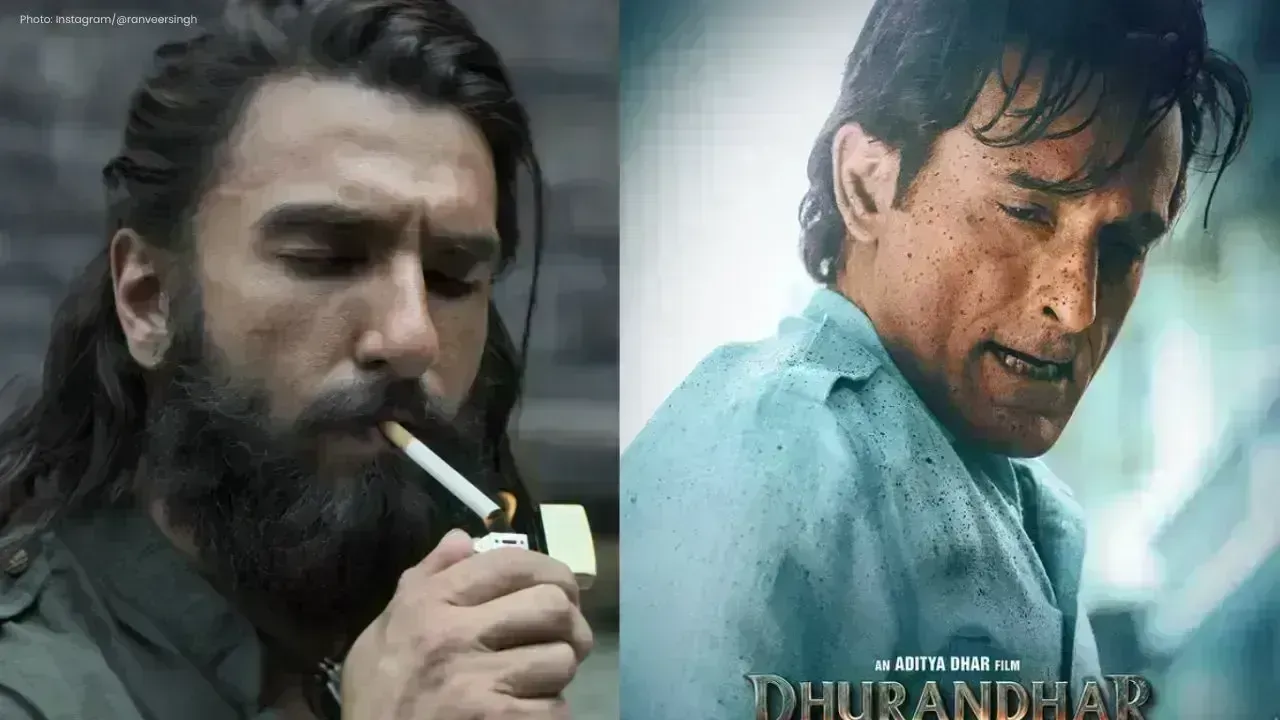

Ranveer Singh’s Dhurandhar Roars Past ₹1100 Cr Worldwide

Ranveer Singh’s Dhurandhar stays unstoppable in week four, crossing ₹1100 crore globally and overtak

Asian Stocks Surge as Dollar Dips, Silver Hits $80 Amid Rate Cut Hopes

Asian markets rally to six-week highs while silver breaks $80, driven by Federal Reserve rate cut ex

Balendra Shah Joins Rastriya Swatantra Party Ahead of Nepal Polls

Kathmandu Mayor Balendra Shah allies with Rastriya Swatantra Party, led by Rabi Lamichhane, to chall

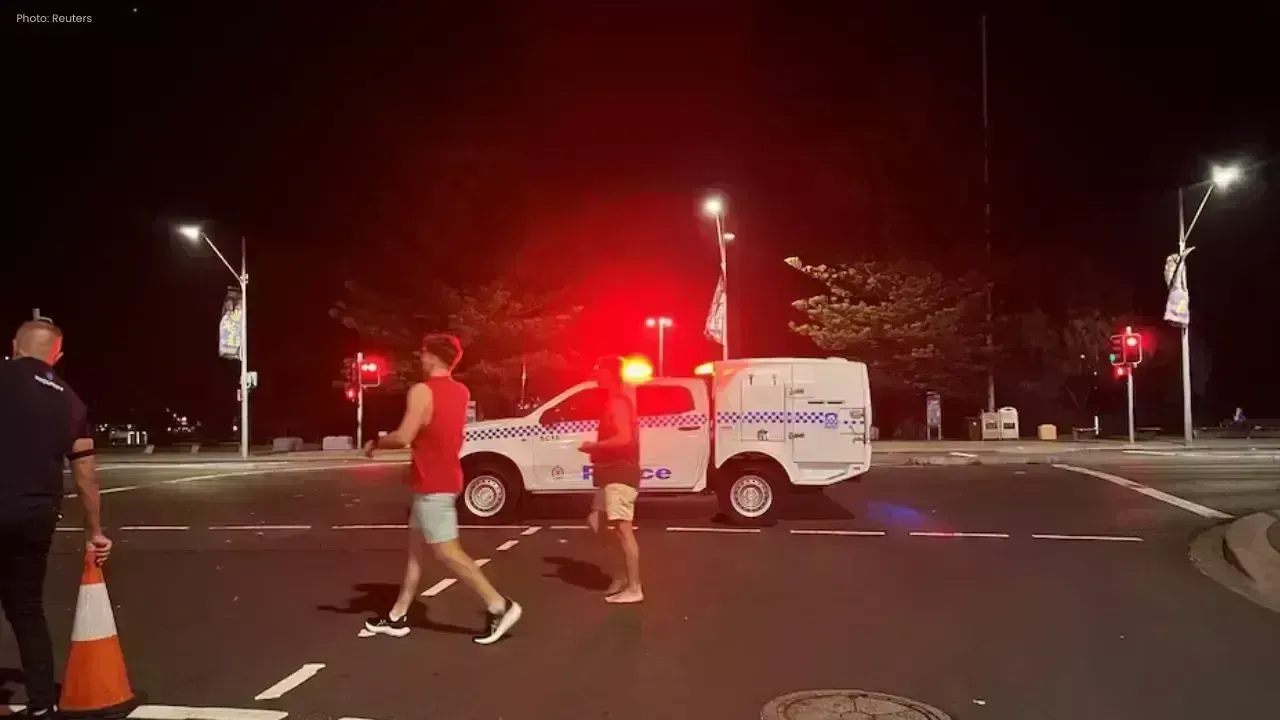

Australia launches review of law enforcement after Bondi shooting

Australia begins an independent review of law enforcement actions and laws after the Bondi mass shoo

Akshaye Khanna exits Drishyam 3; Jaideep Ahlawat steps in fast

Producer confirms Jaideep Ahlawat replaces Akshaye Khanna in Drishyam 3 after actor’s sudden exit ov