You have not yet added any article to your bookmarks!

Join 10k+ people to get notified about new posts, news and tips.

Do not worry we don't spam!

Post by : Anis Farhan

Plastic pollution is no longer a distant, invisible threat — it’s in our rivers, oceans, soil, seafood, and even in our bloodstreams. Across Asia, the problem has exploded over the past two decades, fueled by rapid urbanization, inadequate waste management, and the unrelenting production of single-use plastics.

The crisis is not just environmental — it’s deeply personal. Families are unknowingly consuming microplastics through food and water, fishers are watching their livelihoods crumble, and coastal communities are bearing the brunt of a global waste problem they did not create alone. The scale is vast, the damage is intimate, and the urgency has never been greater.

In cities like Dhaka, Manila, Jakarta, and Mumbai, millions of people live near landfills and open dumps. For waste workers, daily exposure to plastic debris is not just a job hazard — it’s a slow, invisible form of poisoning.

Recent studies have shown alarming levels of microplastics in human blood, with some samples containing hundreds of plastic particles per millilitre. These particles are often small enough to travel through the bloodstream, lodge in organs, and potentially disrupt cellular functions. Scientists are still uncovering the long-term health consequences, but early research points to increased risks of inflammation, hormonal disruption, and even certain cancers.

For many in Asia’s urban poor communities, plastic pollution is not just about litter — it’s a health emergency happening quietly within their own bodies.

The rivers of Asia are among the most plastic-polluted waterways in the world. In India, for instance, research in Gujarat revealed a disturbing truth: fish caught in the Narmada and Mahi rivers contained significant amounts of microplastics, including polypropylene and nylon. These plastics are often mistaken for food by smaller marine organisms, which are then eaten by larger fish — and eventually by humans.

On the eastern coast, studies along the Visakhapatnam shoreline found microplastics in all examined species of fish and shellfish. The plastics included polyethylene, PVC, nylon, and polystyrene — materials common in packaging, fishing gear, and household items.

This contamination is not isolated to India. Similar findings have been reported in Southeast Asia, with studies in the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam showing seafood contamination levels high enough to raise serious public health concerns.

While bottles, bags, and wrappers dominate the conversation around plastic waste, there’s another, less talked-about culprit: nurdles. These small plastic pellets, about the size of a lentil, are the raw material used to make most plastic products.

When shipping accidents occur — as happened recently off the coast of Kerala, India — millions of nurdles can spill into the ocean. They are incredibly difficult to clean up, easily mistaken for fish eggs by marine animals, and capable of absorbing toxic chemicals from the water. Once ingested by fish, turtles, and seabirds, the plastics can cause internal injuries, starvation, and death.

For coastal communities, a nurdle spill can devastate both ecosystems and economies. In Kerala, fishing activities were temporarily halted in affected zones, causing financial hardship for thousands of families already struggling with declining catches.

Plastic pollution is not just an environmental issue — it is an economic one. Fisheries, tourism, and shipping industries suffer billions of dollars in losses each year due to polluted waters, damaged ecosystems, and the cleanup costs that follow.

In coastal tourist hubs like Bali, Boracay, and Phuket, periodic beach cleanups have become almost as common as sunrise yoga sessions. But these efforts, while valuable, only scratch the surface. The deeper problem lies in upstream production and consumption patterns — and in the lack of effective policies to manage plastic waste before it reaches waterways.

Governments across Asia are slowly waking up to the scale of the crisis. Some, like Sri Lanka, have made landmark legal moves — the country’s Supreme Court recently ordered the owners of a ship responsible for a massive nurdle spill to pay $1 billion in compensation. This not only covers immediate environmental restoration but also sets a precedent for holding polluters financially accountable.

In India, state-level initiatives are gaining traction. Andhra Pradesh launched an ambitious “War on Single-Use Plastic” campaign, mobilizing thousands of volunteers to spread awareness about waste segregation and sustainable alternatives. In Varanasi, even the sacred Kashi Vishwanath Temple has banned plastic containers to preserve its heritage environment.

Meanwhile, at the international level, negotiations are underway for a Global Plastics Treaty, aiming to curb plastic production, regulate its transport, and establish liability for spills and pollution incidents.

While policy shifts are important, real change often begins at the community level. Across Asia, grassroots movements are pioneering innovative approaches to reducing plastic waste.

In Manila, youth-led groups organize weekly river cleanups, collecting not just trash but also data that helps map pollution sources. In Indonesia, community cooperatives are turning collected plastic waste into eco-bricks for low-cost housing. In rural Vietnam, women’s associations run education programs teaching families how to reduce dependence on disposable plastics.

These grassroots initiatives show that while top-down policies matter, bottom-up solutions can be equally powerful in shifting habits and protecting ecosystems.

Plastic manufacturers and the wider corporate sector cannot remain passive observers. Many companies have pledged to reduce plastic in their packaging, but progress is uneven. Some major beverage brands, for example, have experimented with refill-and-return systems in parts of Asia, but these programs remain limited in scale.

There is also growing interest in biodegradable alternatives, such as plant-based packaging and compostable films. However, these innovations face cost and infrastructure challenges, particularly in low-income regions where waste segregation is minimal.

In many Asian countries, the rise in plastic waste mirrors changing lifestyles. A growing middle class, faster-paced urban living, and the expansion of e-commerce have all contributed to more single-use packaging in daily life. From takeaway containers to online shopping parcels, convenience often wins over sustainability.

Yet, cultural heritage offers a different perspective. In parts of India, Sri Lanka, and Southeast Asia, serving food on banana leaves or wrapping goods in woven palm is a centuries-old tradition. Reviving such practices could provide locally rooted, low-cost solutions to the plastic problem.

Addressing Asia’s plastic crisis will require a multi-pronged approach:

Reduce Production: Shift away from unnecessary single-use plastics through legislation and market incentives.

Improve Waste Management: Invest in infrastructure to collect, sort, and recycle waste effectively.

Corporate Responsibility: Enforce Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes so manufacturers are accountable for the lifecycle of their products.

Public Awareness: Launch sustained education campaigns that not only inform but also inspire behavior change.

International Cooperation: Coordinate across borders to tackle marine plastic pollution, which knows no national boundaries.

The key is persistence. Quick fixes won’t solve a problem decades in the making — but consistent, systemic action can turn the tide.

The plastic crisis in Asia is vast, but it is not insurmountable. From lawmakers drafting stronger regulations to everyday citizens carrying reusable bags, every action counts.

The stakes are clear: the health of our oceans, the safety of our food, and the well-being of future generations depend on choices we make now. The next time you use — or refuse — a piece of plastic, remember that it is part of a much bigger story. And in that story, your role matters.

This article is based on current research, expert interviews, and recent case studies. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, scientific understanding of microplastics and their health effects is still evolving. Readers are encouraged to consult official environmental reports and local guidelines for the most up-to-date information.

Two Telangana Women Die in California Road Accident, Families Seek Help

Two Telangana women pursuing Master's in the US died in a tragic California crash. Families urge gov

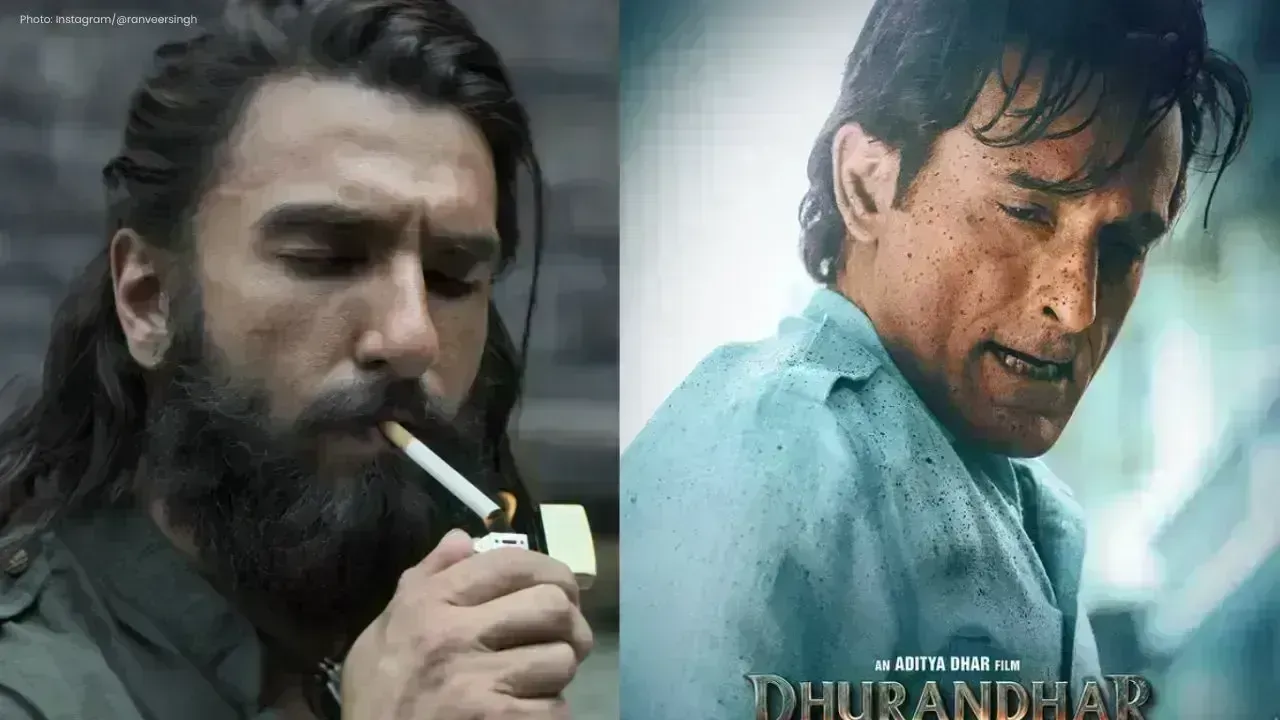

Ranveer Singh’s Dhurandhar Roars Past ₹1100 Cr Worldwide

Ranveer Singh’s Dhurandhar stays unstoppable in week four, crossing ₹1100 crore globally and overtak

Asian Stocks Surge as Dollar Dips, Silver Hits $80 Amid Rate Cut Hopes

Asian markets rally to six-week highs while silver breaks $80, driven by Federal Reserve rate cut ex

Balendra Shah Joins Rastriya Swatantra Party Ahead of Nepal Polls

Kathmandu Mayor Balendra Shah allies with Rastriya Swatantra Party, led by Rabi Lamichhane, to chall

Australia launches review of law enforcement after Bondi shooting

Australia begins an independent review of law enforcement actions and laws after the Bondi mass shoo

Akshaye Khanna exits Drishyam 3; Jaideep Ahlawat steps in fast

Producer confirms Jaideep Ahlawat replaces Akshaye Khanna in Drishyam 3 after actor’s sudden exit ov