You have not yet added any article to your bookmarks!

Join 10k+ people to get notified about new posts, news and tips.

Do not worry we don't spam!

Post by : Anis Farhan

Forests are more than trees. They are biodiversity hotspots, climate regulators, water reservoirs, and homes to millions of people — particularly Indigenous communities whose livelihoods, cultures and identities are deeply intertwined with forest ecosystems. Yet across the world, forests are being cleared, degraded, and converted at alarming rates. The causes are many — commercial agriculture, logging, mining, infrastructure expansion, weak legal protections, and conflicting land uses. This article explores the impacts of deforestation, the rights and role of Indigenous peoples, recent global trends and responses, and proposes paths forward that balance development, justice, and ecological sustainability.

Deforestation refers to the large-scale removal of forest cover, whether by clear-cutting, burning, or conversion of forests to other land uses (agriculture, pasture, infrastructure). Degradation (when forests remain but are damaged) and disturbance (fires, fragmentation) add further harm, sometimes in less visible ways. The consequences are far-reaching:

Climate Impacts: Forests store vast amounts of carbon; their destruction releases carbon dioxide, accelerating climate change. Degradation and disturbance also reduce carbon-sequestering capacity.

Biodiversity Loss: Many species are forest-dependent. As forests shrink or fragment, habitat loss, species extinction, and ecosystem disruption follow.

Water Cycles & Soil Quality: Forests play critical roles in maintaining soil health, preventing erosion, regulating water flows and rainfall patterns. Loss of forest cover often leads to flooding, droughts, and decline in soil fertility.

Livelihoods & Human Health: Indigenous and local communities depend on forests for food, medicine, fuel, clean water, cultural practices, and spiritual life. Deforestation threatens all this. Polluted water, degraded land, loss of traditional medicines, and exposure to invasive pathogens or pollutants are among the human impacts.

Indigenous communities—and more broadly, local forest-dependent communities—play a dual role: many are among the world’s most effective stewards of forest health, yet “on the front lines” of deforestation’s harms. Their rights (to land, consultation, free prior and informed consent) are often weak, contested, or ignored. Key points:

Territorial Stewardship: Studies show that where Indigenous land rights are legally recognized and enforced, deforestation rates tend to be significantly lower. Secondary forest regrowth also tends to happen faster in such territories.

Threats & Pressures: Even in formally recognized areas, threats come from illegal logging, expansion of agricultural frontiers (e.g. cattle ranching, soy, palm oil), mining, roads & infrastructure projects, land grabbing, and weak enforcement.

Cultural & Spiritual Impact: Forests are integral to Indigenous cultures: traditional knowledge, spiritual and ceremonial places, languages tied to natural landscapes, medicinal plants and food sources depend on intact ecosystems. Loss of forests erodes these ties. Health & Well-Being: Loss of forests often correlates with water pollution, respiratory issues from smoke, malnutrition from the loss of forest food sources, increased vulnerability to infectious diseases when habitats are disturbed, exposure to chemicals (e.g. mercury from mining).

Understanding current trends is vital to gauging how urgent the crisis is, and where responses are succeeding or failing.

In 2024, global loss of tropical “pristine forest” reached around 6.7 million hectares, an increase of about 80% over 2023. Major drivers include wildfires, droughts, agricultural expansion. Brazil saw very high losses in the Amazon.

In Brazil, under recent years, deforestation in Indigenous lands increased sharply. One study found a 129% increase in deforestation in Brazilian Amazon Indigenous territories between 2013-2021.

Comparative data show that Indigenous and community lands tend to maintain better forest cover compared to non-Indigenous lands or parts without community management. For example, forests in Indigenous territories in the Amazon sequester more carbon and show lower loss, though this protection is not absolute.

However, even Indigenous territories are under rising pressure from infrastructure (roads), extractive industries, policy rollbacks, fires, and political/institutional inertia. Degradation and disturbance are increasing even where outright deforestation is constrained.

While many countries officially recognize Indigenous rights, in practice there are wide gaps between law and enforcement. Some of these include:

Weak recognition of land titles: Indigenous territories are not always formally recognized or demarcated. Without legal title, communities struggle to defend against incursions.

Lack of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC): Projects on Indigenous land are often approved without proper consultation or in the absence of meaningful participation. This violates international norms and contributes to conflicts.

Policy rollbacks and weakening of safeguards: Some legislation changes are making it easier for corporations to convert forest land with fewer environmental or social protections; some laws retroactively legalize past deforestation.

Violence, criminalization, intimidation: Indigenous leaders, forest defenders, local activists often face threats, legal harassment, violence. Land disputes escalate into conflict when rights are challenged.

Below are some of the global strategies being pursued, with examples of both success and limitations.

Countries and international bodies have set aside protected areas to conserve biodiversity and forest health. These include national parks, reserves, biosphere zones. In some cases, Indigenous communities are co-managers or even lead management.

Limitations: Sometimes such areas displace communities without ensuring their rights; sometimes enforcement is weak; sometimes extractive pressures continue illegally.

In regions like Latin America, legal recognition of Indigenous territories has shown to reduce deforestation and promote forest regrowth. Secure land tenure helps Indigenous people enforce stewardship.

New tools including satellite imagery, deforestation alerts, mapping, participatory monitoring help detect illegal activities or degradation early. Indigenous people are using freely available tools to document incursions and push back. Example: the Saamaka in Suriname using satellite data to show logging encroachment.

Climate finance mechanisms (such as REDD+, carbon credit schemes) aim to incentivize forest conservation. Global treaties, UN declarations (UNDRIP), biodiversity frameworks push for recognition of Indigenous rights.

Limitations: Many offset or carbon projects fail to deliver promised reductions, or do not fairly involve or compensate Indigenous communities. Baselines are contested. Projects may lack transparency.

Indigenous rights organizations, NGOs, grassroots movements have forced public awareness, legal rulings, changes in policy. They mobilize globally to pressure governments and corporations. Global media, reports, and litigation have led to some victories.

Here are several concrete cases that illustrate the dynamic between deforestation, Indigenous rights, and response.

In Suriname, despite a legal decision from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights recognizing Indigenous Saamaka territorial rights, tree cover loss within those territories has continued, especially due to logging and mining concessions granted nearby without adequate consent. Satellite data has documented encroachment, road building, and forest loss in the Saamaka territory.

Indigenous territories in the Amazon have generally fared better in forest preservation than many other lands. But under recent administrations, deforestation inside these areas has surged, both from illegal activity and regulatory relaxations. Road networks penetrating Indigenous lands strongly correlate with increased deforestation.

Across Suriname, Indonesia, Peru and other countries, Indigenous and local communities are using satellite tools (e.g. Global Forest Watch, mobile apps) to monitor deforestation in near real time, document breaches, and bring evidence to governmental or legal authorities for action. wri.org

From the evidence:

Recognized land rights reduce deforestation rates and promote forest recovery. Secure tenure gives communities legal standing to claim protection and resist illegal incursions.

Indigenous territories act as carbon sinks and help meet climate mitigation goals: preserving biodiversity, storing carbon, regulating water, etc.

Indigenous communities often have traditional ecological knowledge that yields sustainable land use models — controlled burns, selective extraction, agroforestry, sacred groves, etc.—that maintain ecological integrity.

When Indigenous rights are denied or undermined, deforestation accelerates, and the social, cultural, environmental harms multiply.

Despite progress, many hurdles remain:

Weak enforcement: Even where laws exist, enforcement is often lax due to corruption, lack of capacity, political resistance.

Conflicts of interest: Governments or powerful private interests (agribusiness, mining, timber companies) often benefit financially from deforestation. Incentives may push in favor of forest conversion.

Displacement, loss of livelihood: Some conservation or protected area policies have been implemented without properly involving Indigenous communities, sometimes displacing them or limiting access to forests they rely on.

Climate change-induced pressures: Fires, drought, pest outbreaks also increase forest vulnerability, sometimes beyond what human governance systems can manage.

International finance and carbon markets issues: Projects may overstate preservation, fail to properly account for baseline deforestation, or fail to distribute benefits fairly.

To confront the deforestation crisis in a just, sustainable manner, several paths are critical:

Secure Legal Land Rights & Ownership

Formal recognition of Indigenous land titles, equitable legal frameworks, demarcation and enforcement. Ensuring that FPIC (Free, Prior, Informed Consent) is respected whenever new projects or land uses are proposed.

Strengthen Monitoring & Transparency

Use satellite data, local participatory monitoring, mapping, mobile technology to detect and report deforestation, illegal logging, land conversion. Make the data public and usable. Empower Indigenous and local communities to use such tools.

Accountability & Legal Recourse

Ensure that offenders — illegal loggers, land grabbers, corporations violating rights — are held accountable. Judicial systems, human rights bodies, international advocacy can support communities in bringing legal challenges.

Integrate Indigenous Knowledge & Culture

Conservation policies should build on Indigenous ecological knowledge — traditional land-use practices, cultural attachments, customary laws. Co-management or community-led management often yields better ecological outcomes.

Align Incentives: Finance, Markets & Policy

Improve climate finance flows to Indigenous and forest-dependent communities. Design carbon and biodiversity offset schemes that respect rights, provide fair compensation, and are transparent. Governments need policies that align agricultural, infrastructure, and development plans with forest conservation.

Global Cooperation and Pressure

International treaties, agreements, donor commitments, trade rules (e.g. deforestation-free supply chains), must all push for stronger protections and enforcement. Consumer awareness and corporate responsibility also matter.

Resilience Building

Invest in forest restoration, adaptive management, prevention of fires, protecting watershed areas. Support livelihoods alternatives for Indigenous communities impacted by loss of forest resources, so that pressure to deforest is reduced.

While the scale of the challenge is massive, there are promising developments:

Some nations are committing to ambitious forest conservation targets, e.g. protecting large percentages of forest cover, securing Indigenous land rights, or expanding protected area networks.

Technology democratization: satellite imagery, mobile tools, mapping platforms are increasingly accessible, helping people monitor forests themselves, often in near-real time.

Growing recognition in international frameworks of the role of Indigenous Peoples and the necessity of rights-based conservation.

Consumer pressure and private sector shifts: more companies are responding to demands for deforestation-free supply chains. Sustainability certifications, consumer awareness, and trade regulations are starting to put pressure on agribusiness to avoid forest destruction.

If these trends gain momentum, and if action is taken with justice and inclusion, there is real potential to slow forest loss, restore degraded lands, and ensure that Indigenous communities not only survive but thrive.

Deforestation is one of the defining environmental and human rights challenges of our epoch. It is not just an ecological crisis but a crisis of justice — for Indigenous peoples, for biodiversity, for climate stability, and for future generations. Ensuring that Indigenous rights are recognized, protected, and upheld is not a side issue but central to stopping deforestation.

Global responses must move beyond declarations: legal reforms, enforcement, participatory monitoring, fair finance, and collaborative governance are all essential. Without these, forests will continue to disappear, cultures will unravel, and climate goals will become ever more distant.

The path forward demands both moral clarity and rigorous action. Forests are not only carbon reservoirs; they are living entities, cultural repositories, and places of hope. The world must act now — decisively and justly — to defend them.

This article is based on publicly available data and recent academic, journalistic, and policy sources as of mid-2025. It is intended for informational purposes only. The content does not represent official policy or legal advice.

Ashes Failure Puts Brendon McCullum Under Growing England Pressure

England’s Ashes loss has sparked questions over Bazball, as ECB officials review Test failures and B

Kim Jong Un Celebrates New Year in Pyongyang with Daughter Ju Ae

Kim Jong Un celebrates New Year in Pyongyang with fireworks, patriotic shows, and his daughter Ju Ae

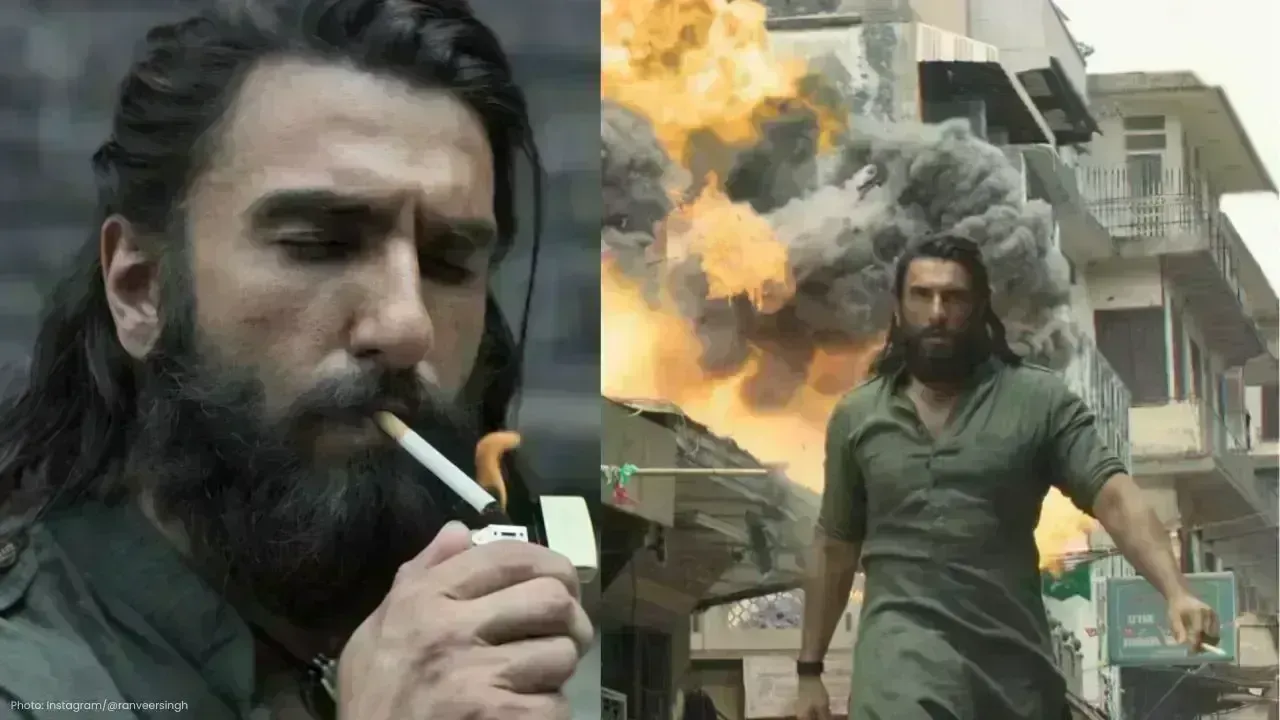

Dhurandhar Day 27 Box Office: Ranveer Singh’s Spy Thriller Soars Big

Dhurandhar earns ₹1117 crore worldwide by day 27, becoming one of 2026’s biggest hits. Ranveer Singh

Hong Kong Welcomes 2026 Without Fireworks After Deadly Fire

Hong Kong rang in 2026 without fireworks for the first time in years, choosing light shows and music

Ranveer Singh’s Dhurandhar Hits ₹1000 Cr Despite Gulf Ban Loss

Dhurandhar crosses ₹1000 crore globally but loses $10M as Gulf nations ban the film. Fans in holiday

China Claims India-Pakistan Peace Role Amid India’s Firm Denial

China claims to have mediated peace between India and Pakistan, but India rejects third-party involv