You have not yet added any article to your bookmarks!

Join 10k+ people to get notified about new posts, news and tips.

Do not worry we don't spam!

Post by : Anis Farhan

Southeast Asia is at a turning point in its energy story. Rapid population growth, industrial expansion, and urbanization have placed the region among the fastest-growing energy markets in the world. With coal still a dominant source of electricity and renewable adoption moving at an uneven pace, governments are searching for alternatives that balance affordability, reliability, and sustainability. Nuclear energy, once dismissed in the region due to high costs and public safety concerns, is suddenly back on the table—this time in a new form.

Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) are being hailed as the next frontier in nuclear technology. Unlike traditional nuclear plants, these reactors are smaller, more flexible, and considered safer by design. For Southeast Asian nations, SMRs offer a potential solution to two urgent challenges: how to meet skyrocketing energy demand and how to decarbonize without sacrificing economic competitiveness. The question is whether SMRs can move from promising theory to widespread reality in this diverse and complex region.

The conversation around nuclear energy in Southeast Asia is not new. Countries such as Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia have flirted with nuclear ambitions for decades, often announcing bold plans only to scale them back due to safety concerns, financing hurdles, or public opposition. The Fukushima disaster in 2011 intensified skepticism, pushing nuclear further down the energy agenda.

But the global energy landscape has shifted dramatically in the past decade. Climate change pressures, rising fossil fuel prices, and the intermittency of solar and wind have forced policymakers to revisit nuclear options. Unlike renewables, nuclear provides baseload power—constant, uninterrupted energy supply that industrial economies rely on. And unlike coal, it does so with minimal greenhouse gas emissions.

This shift explains why Southeast Asian governments are cautiously re-examining nuclear power, with SMRs becoming a focal point of interest.

SMRs represent a departure from traditional nuclear design. Instead of building massive, billion-dollar plants, SMRs are designed as compact units, often factory-assembled and transportable. They typically generate between 50 to 300 megawatts of power each, compared to over 1,000 megawatts for conventional reactors.

Key advantages include:

Scalability: Nations can deploy SMRs gradually, adding capacity as demand grows.

Safety Features: Most SMRs incorporate passive cooling and automated shutdown mechanisms, reducing risks of catastrophic failures.

Lower Capital Costs: With modular construction and smaller footprints, upfront investments are lower, making nuclear more accessible to developing economies.

Flexibility: SMRs can be located closer to demand centers, or even integrated with industrial zones, reducing transmission needs.

For Southeast Asia, where geography includes islands, remote regions, and dense urban centers, the adaptability of SMRs aligns well with local energy challenges.

Energy demand in Southeast Asia is expected to nearly double by 2040, according to regional forecasts. Coal remains cheap and widely available, but its environmental costs are no longer politically or socially sustainable. Natural gas, while cleaner, faces volatility in global prices. Renewables are growing but face storage and grid integration challenges.

SMRs could become the missing piece in this puzzle. They provide reliable baseload power to complement intermittent renewables, potentially creating a balanced and resilient energy mix. For island nations like the Philippines or archipelagos like Indonesia, SMRs could deliver power to isolated communities without relying on long-distance transmission.

However, every opportunity comes with its hurdles.

While SMRs look promising on paper, several roadblocks stand in the way of widespread adoption:

High Initial Costs: Although cheaper than traditional nuclear, SMRs still require significant upfront investment compared to coal or renewables.

Regulatory Frameworks: Most Southeast Asian countries lack comprehensive nuclear regulatory bodies or safety oversight mechanisms. Building these institutions will take time and resources.

Public Perception: Decades of fear around nuclear safety persist. Fukushima remains a vivid memory, and local opposition could stall projects.

Waste Management: Even small reactors generate radioactive waste, and Southeast Asia currently lacks long-term disposal strategies.

Technology Dependence: SMR technology is still emerging, with most designs being developed in North America, Europe, or Russia. Southeast Asian nations risk becoming dependent on foreign suppliers.

These challenges explain why SMRs are being considered cautiously rather than embraced wholesale.

Vietnam: Once planned to build full-scale nuclear plants, Vietnam shelved its projects due to costs. Today, it is revisiting nuclear options through SMRs, with feasibility studies underway.

Indonesia: With its growing population and heavy reliance on coal, Indonesia is exploring SMRs for both urban centers and remote islands. Partnerships with foreign technology providers are in early talks.

Philippines: Energy shortages and reliance on imported fuels are pushing Manila to consider nuclear again. The government is actively studying SMR deployment as part of its 2030 energy strategy.

Thailand: While cautious, Thailand has included nuclear in its long-term energy roadmap, considering SMRs as a potential option in the 2030s.

Malaysia: Though not a frontrunner, Malaysia is monitoring SMR developments closely as part of its sustainable energy goals.

No country in the region has yet committed to large-scale SMR projects, but exploratory agreements and pilot programs are gaining momentum.

The region can draw lessons from early SMR adopters elsewhere:

Canada and the U.S.: Both are testing SMRs to complement renewables and provide power in remote areas. Their progress could provide blueprints for regulatory frameworks.

Russia: Operates a floating SMR plant in the Arctic, proving that modular reactors can function in extreme and isolated conditions.

China: Has aggressively invested in SMR development, with operational pilot plants already underway. Its approach could influence neighboring Asian countries.

For Southeast Asia, partnerships with these nations will be critical—not just for technology, but also for knowledge transfer in safety, regulation, and public engagement.

Adopting SMRs isn’t just about electricity. It carries broader economic and geopolitical implications:

Energy Security: Reduces dependence on imported fuels like coal and LNG.

Industrial Growth: Reliable baseload power supports manufacturing and digital economies.

Climate Commitments: Helps nations meet emissions targets under the Paris Agreement.

Geopolitical Partnerships: Countries that adopt SMRs may deepen ties with nuclear technology providers, influencing foreign policy.

In this sense, SMRs are not just an energy choice—they’re a strategic one.

For SMRs to succeed in Southeast Asia, governments must address multiple fronts simultaneously:

Policy Development: Establishing clear nuclear regulations and safety agencies.

Public Communication: Engaging communities to build trust and counter misinformation.

Regional Cooperation: ASEAN could play a role in harmonizing nuclear safety standards and pooling resources for waste management.

Technology Transfer: Ensuring local capacity-building rather than complete dependence on foreign expertise.

Financing Models: Exploring public-private partnerships to offset initial costs.

The transition won’t be fast. Even under optimistic timelines, SMRs are unlikely to play a significant role before the mid-2030s. Yet the decisions made today will shape the region’s energy trajectory for decades.

Southeast Asia’s nuclear resurgence is no longer just a distant possibility. As energy demands soar and sustainability pressures mount, SMRs have entered the spotlight as a potential game-changer. They promise cleaner, safer, and more adaptable nuclear power—qualities that align closely with the region’s diverse energy challenges.

Still, ambition must be tempered with realism. Regulatory readiness, financial viability, public trust, and waste management all remain hurdles that cannot be ignored. The future of SMRs in Southeast Asia will depend less on technology itself and more on governance, collaboration, and political will.

If nations succeed, SMRs could become a cornerstone of Southeast Asia’s energy transition, ensuring that growth and green goals move hand in hand. If they falter, the region risks locking itself further into fossil fuel dependency. Either way, the nuclear question is back—and this time, it may find a more receptive audience.

This article is for informational and editorial purposes only. It does not provide financial, policy, or technical advice. Readers are encouraged to consult energy experts and official reports before drawing conclusions from the topics discussed.

Rashmika Mandanna, Vijay Deverakonda Set to Marry on Feb 26

Rashmika Mandanna and Vijay Deverakonda are reportedly set to marry on February 26, 2026, in a priva

FIFA Stands by 2026 World Cup Ticket Prices Despite Fan Criticism

FIFA defends the high ticket prices for the 2026 World Cup, introducing a $60 tier to make matches m

Trump Claims He Ended India-Pakistan War, Faces Strong Denial

Donald Trump says he brokered the ceasefire between India and Pakistan and resolved eight wars, but

Two Telangana Women Die in California Road Accident, Families Seek Help

Two Telangana women pursuing Master's in the US died in a tragic California crash. Families urge gov

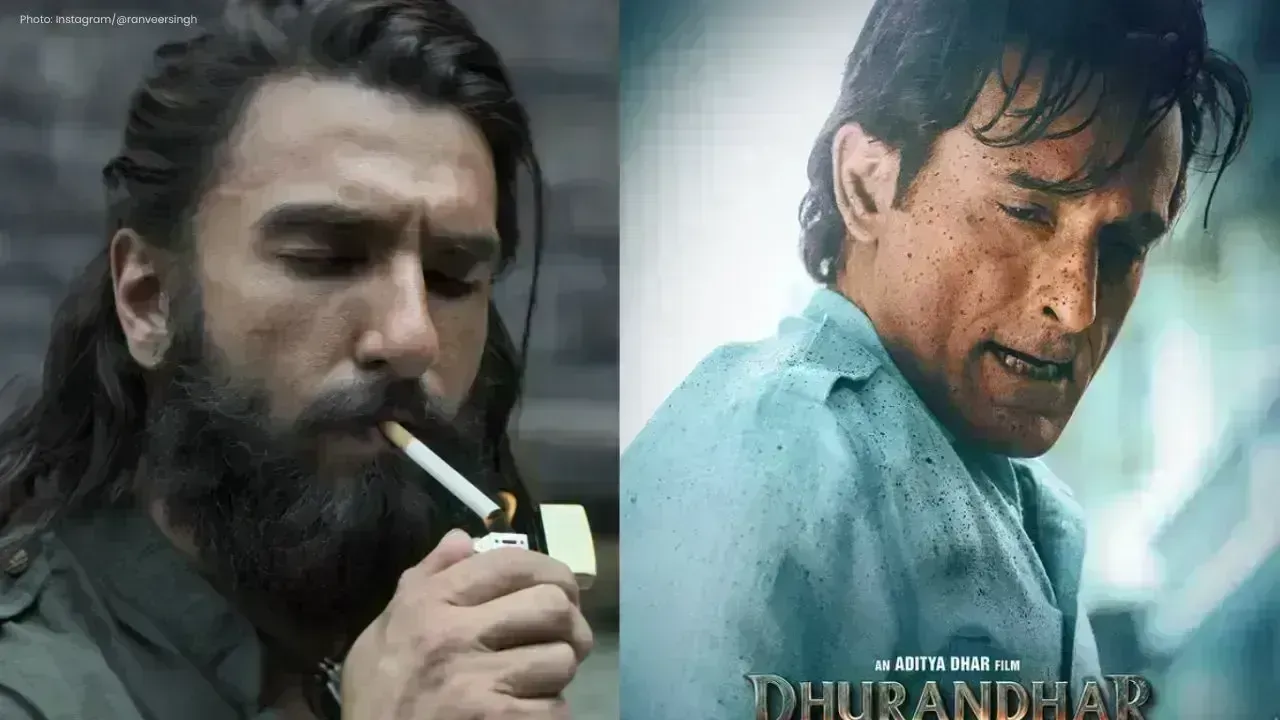

Ranveer Singh’s Dhurandhar Roars Past ₹1100 Cr Worldwide

Ranveer Singh’s Dhurandhar stays unstoppable in week four, crossing ₹1100 crore globally and overtak

Asian Stocks Surge as Dollar Dips, Silver Hits $80 Amid Rate Cut Hopes

Asian markets rally to six-week highs while silver breaks $80, driven by Federal Reserve rate cut ex