You have not yet added any article to your bookmarks!

Join 10k+ people to get notified about new posts, news and tips.

Do not worry we don't spam!

Post by : Anis Farhan

In the far corners of Southeast Asia — from the rice fields of Isaan to the jungles of Kalimantan — a quiet educational revolution is taking shape. Here, in classrooms with creaky desks and patchy electricity, technology is making its way into the hands of students once left behind. Laptops, tablets, learning apps, and low-bandwidth content delivery platforms are slowly transforming how children in rural regions access education.

But behind this digital promise lies a persistent question: Can EdTech truly level the playing field between urban privilege and rural disadvantage? Or will it further entrench existing inequities? Across ASEAN nations, the deployment of educational technology in rural classrooms is gaining momentum — but its success depends on infrastructure, policy, pedagogy, and above all, local empowerment.

Southeast Asia’s rapid economic growth has not been matched by equal progress in rural education. Students in urban centers like Bangkok, Jakarta, or Kuala Lumpur often attend well-funded schools with trained teachers and strong curricular support. In contrast, rural learners face a litany of challenges: under-resourced schools, teacher shortages, limited transportation, and in some cases, no access to formal education beyond primary level.

The result is a stark disparity in academic achievement and long-term opportunity. National assessments consistently show lower test scores and literacy rates among students in rural and remote areas. The COVID-19 pandemic, which forced a shift to online learning, only widened this divide — exposing the lack of digital infrastructure and technological access in non-urban areas.

Recognizing the need for bold interventions, governments and NGOs across the ASEAN region are turning to EdTech as a tool to bridge the gap. Initiatives like Thailand’s “Distance Learning via Satellite” (DLTV), Indonesia’s “Rumah Belajar” platform, and Malaysia’s “Digital Education Policy” aim to bring high-quality digital content to remote learners.

These efforts are not just about hardware — though device distribution remains important. The real shift is in delivering localized, culturally relevant, and curriculum-aligned content through accessible platforms. Mobile-first applications, offline video modules, and radio-based learning programs are being designed to meet rural realities where internet connectivity is weak or intermittent.

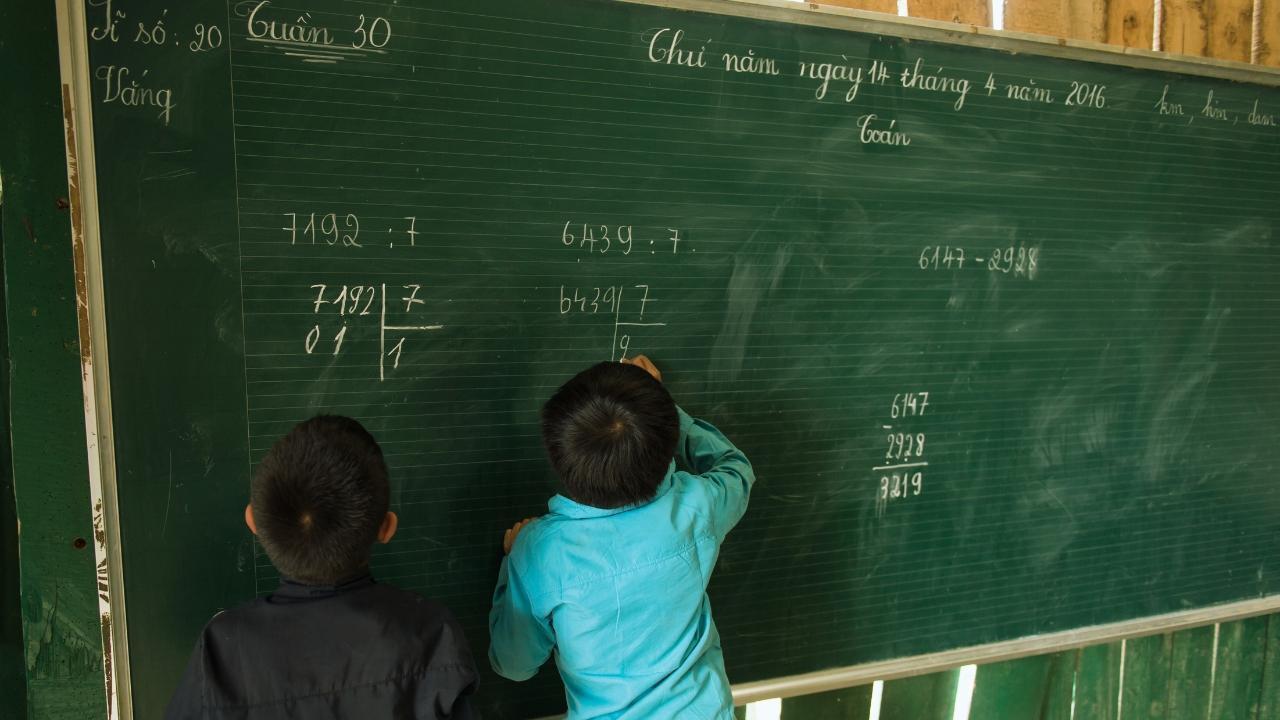

For instance, in the Philippines, community-based learning hubs have been set up with solar-powered tablets preloaded with educational videos. In Vietnam, EdTech startups are experimenting with SMS-based quizzes for students with no smartphone access. These innovations show that digital learning doesn’t have to be flashy — it just has to be functional.

Technology alone cannot drive transformation. Teachers remain central to rural education — not only as content facilitators but also as community figures and mentors. Yet, many rural educators are undertrained in digital tools and pedagogical strategies for blended learning.

Efforts to digitize education must therefore prioritize teacher capacity-building. In Malaysia and Indonesia, teacher training programs are incorporating modules on digital literacy and tech-assisted instruction. Peer-to-peer learning networks are emerging, where rural teachers share experiences and practical solutions online.

Still, challenges persist. Many teachers feel overwhelmed by the dual pressures of delivering standard curricula while adapting to new tools. Without proper support, EdTech risks becoming another burden rather than a solution. Governments must ensure that technological rollouts are accompanied by sustained professional development and mentorship.

One of the biggest barriers to rural EdTech implementation is connectivity — both in terms of internet and electricity. Despite mobile penetration increasing across ASEAN, there are still many “last mile” communities where 4G signals are weak, power is unreliable, and digital literacy remains low.

To address this, countries like Laos and Cambodia are investing in satellite-based internet, mobile learning vans, and mesh networks. Tech companies and donors are also stepping in, providing low-cost routers and solar-charging kits to hard-to-reach schools.

But physical access is only part of the puzzle. True digital equity involves affordability, maintenance, and long-term sustainability. Devices break. Software updates fail. Data plans are expensive. A one-time distribution campaign will not ensure lasting impact unless these realities are addressed through localized planning and recurrent funding.

Another important dimension of EdTech in rural settings is the need for culturally relevant content. Many platforms are built with urban students in mind — using language, examples, and visuals that feel foreign to rural learners. This disconnect reduces engagement and reinforces a sense of marginalization.

In response, new platforms are incorporating local languages, regional dialects, and indigenous knowledge systems into their digital curricula. In Thailand’s north, e-learning modules include traditional agricultural practices. In Sabah, Malaysia, students can access interactive lessons in Kadazandusun and Iban. These inclusive models reinforce pride in local identity while improving educational outcomes.

While the potential of EdTech is undeniable, its long-term success in rural ASEAN classrooms hinges on rigorous impact assessment. Are students learning better? Are dropout rates declining? Are digital tools being used meaningfully or superficially?

Policymakers must move beyond flashy announcements and focus on data-driven interventions. Monitoring frameworks should include feedback loops from students, teachers, and parents. More importantly, rural communities must be seen not just as recipients but as co-designers of educational innovation.

If implemented thoughtfully, EdTech can do more than deliver content — it can empower. It can connect isolated students to the world, give voice to indigenous knowledge, and prepare rural youth for a digital future without erasing their cultural roots.

This article is for general informational and editorial purposes only. It does not represent the views of any government, NGO, or EdTech company. Readers should consult local education authorities and verified policy sources for guidance.

Minimarkets May Supply Red and White Village Cooperatives

Indonesia’s trade minister says partnerships with minimarkets and distributors can strengthen villag

South Africa vs West Indies Clash Heats Up T20 World Cup 2026

Unbeaten South Africa and West Indies meet in a high-stakes Super 8 match at Ahmedabad, with semi-fi

Thai AirAsia Targets Growth Through China & Long-Haul Routes

Thai AirAsia aims 6-9% revenue growth in 2026 expanding domestic flights and new international route

India Ends Silent Observer Role Emerges Key Player in West Asia

From passive energy buyer to strategic partner India’s diplomacy in West Asia now commands trust inf

Indian Students Stuck In Iran Amid US-Iran Tensions And Exam Worries

Rising US-Iran tensions leave Indian students stranded, fearing missed exams could delay graduation

India Says J&K Budget Exceeds Pakistan’s IMF Bailout

India slammed Pakistan at UNHRC, stating J&K’s development budget exceeds Pakistan’s IMF bailout and