You have not yet added any article to your bookmarks!

Join 10k+ people to get notified about new posts, news and tips.

Do not worry we don't spam!

Post by : Anis Farhan

In the past, moments were cherished in memory or shared through conversation. Today, we pull out our smartphones to take a picture or record a video, often before we've fully experienced the moment itself. The constant presence of a camera in our hands means that life is increasingly filtered through a lens—both literally and metaphorically. Instead of living in the present, many of us are driven by the urge to document it.

This new culture of constant documentation has altered not just how we experience events, but how we remember them. We are more likely to recall events we've photographed or filmed, but often through the image or clip rather than the actual memory. This blurring of lived experience and digital record can reshape our sense of reality.

The psychology of memory suggests that taking photos can interfere with how we recall experiences. Known as the “photo-taking impairment effect,” studies have found that people who take photos of an object are less likely to remember the object than those who simply observe it. In other words, we might rely too heavily on our cameras to remember for us.

However, smartphones also serve as digital memory vaults. They help preserve moments we might otherwise forget—first birthdays, travels, family dinners, even mundane routines. With a quick scroll, we’re transported back in time. The convenience of cloud storage and facial recognition makes these memories instantly retrievable and even organized by emotion, event, or person.

Smartphones have also contributed to the rise of performative memory—where people craft moments specifically for the camera. From travel to birthdays to protests, there is now an element of performance in our behavior. A hike isn't complete until there’s a selfie at the summit. A meal isn't memorable unless it’s Instagram-worthy.

This performance shapes not just our actions but how we remember them. When a memory is created with an audience in mind, it often becomes curated, edited, and filtered for external approval. Over time, we may remember not the genuine moment but the version we shared online.

The ubiquity of smartphone cameras also challenges our ideas of privacy. Events once considered private—funerals, hospital visits, intimate conversations—can now be recorded and shared in seconds. Children grow up with their lives documented and broadcast, often without their consent.

At the same time, smartphones have enabled more intimate modes of memory-sharing. Private photo albums, disappearing messages, and live video calls allow people to connect and remember together across distances. Grandparents can watch their grandchildren grow up from miles away. Old friends can relive college memories with a few swipes.

One of the biggest shifts in the smartphone era is how algorithms now control our memories. Apps like Google Photos, Apple Photos, and Instagram curate “memories” for us, sending automated slideshows or reminders about moments from years past. These algorithm-driven memories shape how we reflect on our lives—what we see, what we revisit, what we forget.

While this can be a joyful experience, it also raises concerns. What happens when an unwanted memory resurfaces? What if our sense of identity becomes shaped not by choice but by code?

The cultural implications of this shift go beyond individuals. Globally, smartphone cameras have democratized documentation. People from every corner of the world can now capture and share their reality—from natural disasters to political protests to street celebrations. These personal records collectively form a decentralized memory of our time.

However, this also introduces challenges. Digital manipulation, deepfakes, and misinformation can distort collective memory. In the wrong hands, smartphone footage can be used for surveillance, propaganda, or censorship. The same tool that empowers can also control.

So how do we find balance in this camera-saturated world? The answer might lie in intentionality. Choosing when to document and when to simply be present. Learning to use our phones as tools of remembrance, not replacements for memory.

Many are now practicing "tech mindfulness"—limiting screen time, turning off notifications, and putting the phone away during significant moments. Others are exploring analog alternatives: disposable cameras, journals, or simply creating shared moments without documentation.

Younger generations have grown up with smartphones and are often more fluent in digital memory-making. They understand how to curate an online persona, how to edit videos for social platforms, and how to use filters as forms of expression. For them, memory isn’t just about what happened but how it’s presented.

Older generations, by contrast, may place more emphasis on physical memory—photo albums, handwritten letters, home videos. This generational gap raises interesting questions about which memories endure and which fade with platforms, formats, and devices.

Over-documentation has mental health implications. The pressure to present a perfect life can lead to anxiety, insecurity, and burnout. Always chasing the next photo-worthy moment can prevent us from appreciating the now. Our brains need space to wander, to reflect, and to forget. Memory is as much about forgetting as it is about remembering.

By flooding our minds and devices with constant content, we risk creating digital noise instead of meaningful recollections. We may end up with thousands of images and videos—yet struggle to recall how we truly felt in those moments.

As smartphone cameras continue to advance—bringing 3D imaging, AI-powered editing, and augmented reality—the boundary between memory and media will blur further. We may soon have the ability to revisit memories in immersive virtual environments or use AI to recreate lost moments.

But with this power comes responsibility. We must ask ourselves: Are we documenting life to preserve it, or are we shaping it to look a certain way? Do we own our memories, or are we outsourcing them to machines?

The answer may not be simple, but the question is essential.

This article is a human-written editorial and reflects general analysis on the topic of technology and memory. It is not intended as scientific or psychological advice.

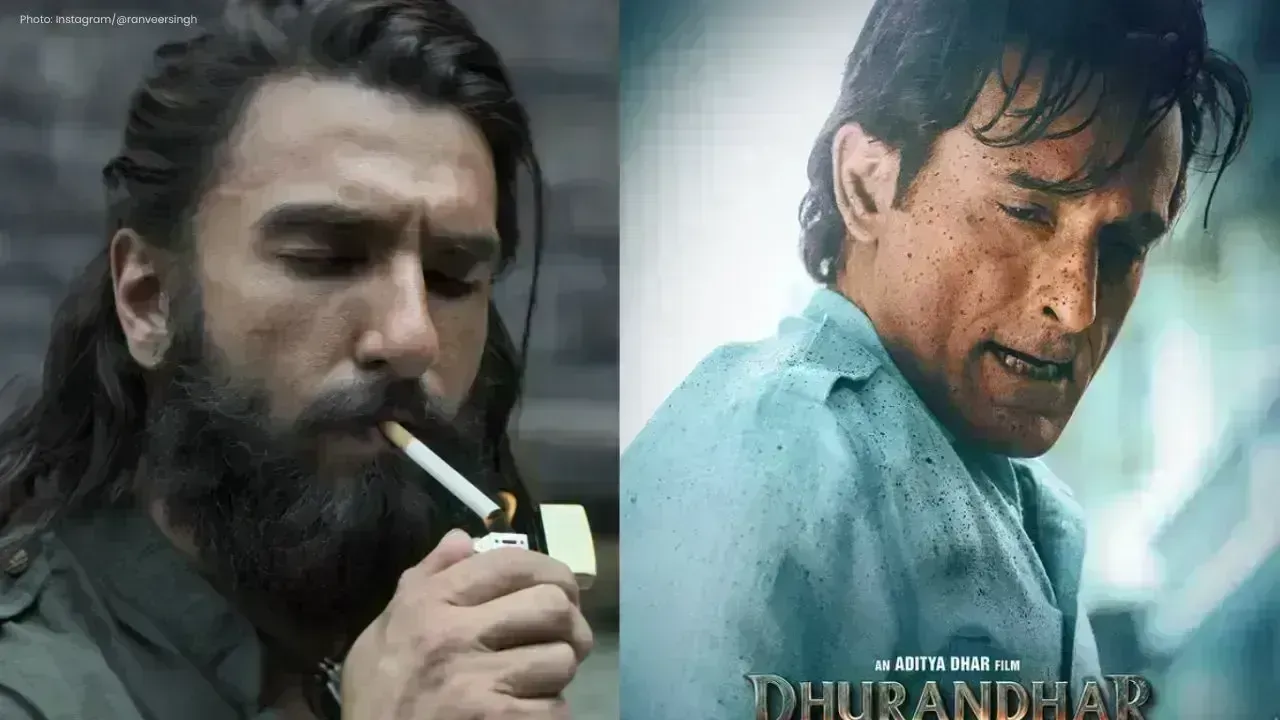

Ranveer Singh’s Dhurandhar Roars Past ₹1100 Cr Worldwide

Ranveer Singh’s Dhurandhar stays unstoppable in week four, crossing ₹1100 crore globally and overtak

Asian Stocks Surge as Dollar Dips, Silver Hits $80 Amid Rate Cut Hopes

Asian markets rally to six-week highs while silver breaks $80, driven by Federal Reserve rate cut ex

Balendra Shah Joins Rastriya Swatantra Party Ahead of Nepal Polls

Kathmandu Mayor Balendra Shah allies with Rastriya Swatantra Party, led by Rabi Lamichhane, to chall

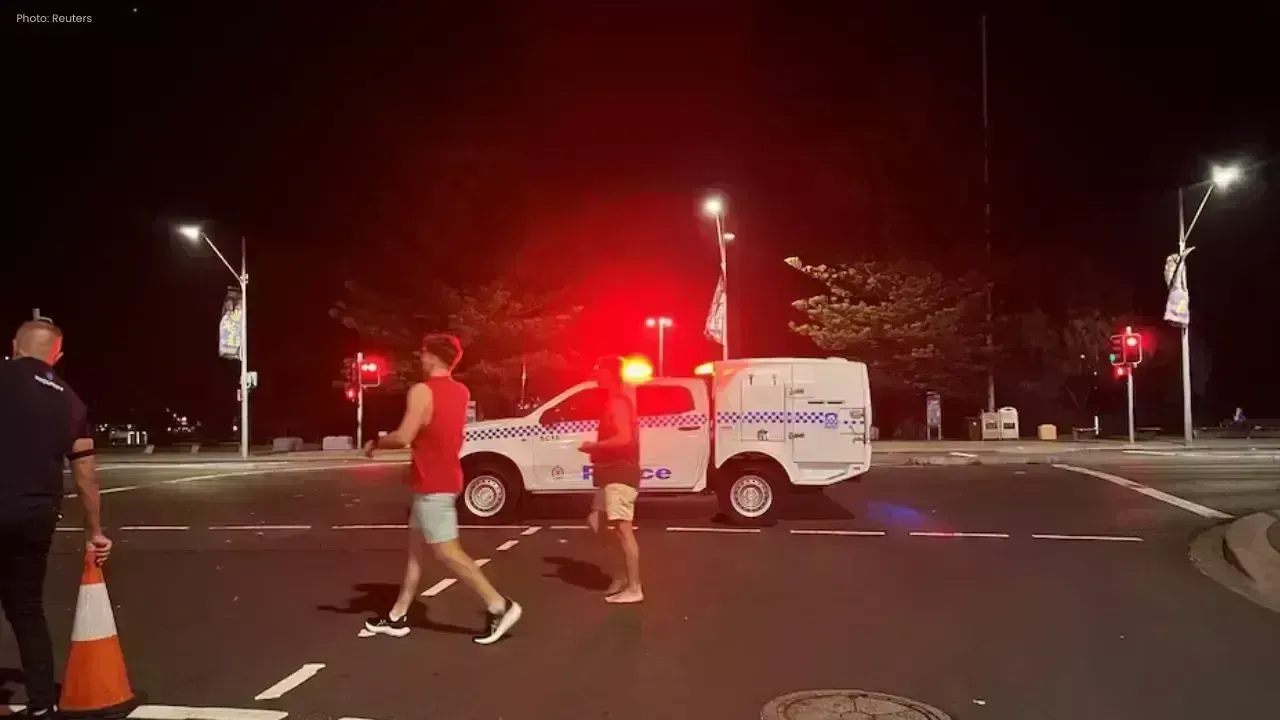

Australia launches review of law enforcement after Bondi shooting

Australia begins an independent review of law enforcement actions and laws after the Bondi mass shoo

Akshaye Khanna exits Drishyam 3; Jaideep Ahlawat steps in fast

Producer confirms Jaideep Ahlawat replaces Akshaye Khanna in Drishyam 3 after actor’s sudden exit ov

Kapil Sharma’s Kis Kisko Pyaar Karoon 2 to Re-release in January 2026

After limited screens affected its run, Kapil Sharma’s comedy film Kis Kisko Pyaar Karoon 2 will ret